Building a matrix-multiplication kernel from scratch using CUDA and applying it to Neural Networks

This project took 8 weeks, during which I had to do research into a topic of my choosing and make an accessible API for using the result in different projects. I have also published an article of this research.

In the past I have done quite some projects regarding neural networks (NN). Most of the time I made use of PyTorch or Tensorflow, but I have also made Neural Network classes myself. I made them myself to deepen my understanding of them, but never used the GPU to do it. Before this research project I had not used the GPU for much, other than for a couple of OpenGL shaders. Over the last couple of weeks I decided to change that and build a general matrix multiplications kernel (GEMM) on the GPU using CUDA.

GPU Introduction

Before we get into the actual GEMM computations, we will first take a look at what the GPU offers and why it is so powerful in executing parallel operations.

Hardware layout

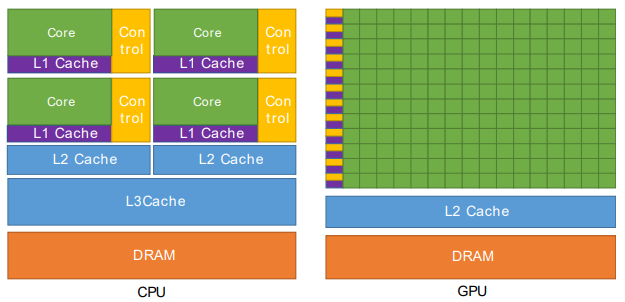

The main difference between a CPU and GPU can be seen in the image below. The CPU has a couple of really powerful cores and 3 caches before reaching DRAM, while the GPU has a much larger amount of cores that are less powerful and not as many caches before reaching DRAM. The large amount of cores is what makes the GPU such a powerful parallel processing machine. This is perfect for GEMM, because the elements of the output matrix are independent from each other (they can be calculated in parallel).

The only thing about caches and DRAM you need to know for the rest of this article, is that the further away the cache is, the longer it takes to access that memory. E.g. the L2 cache is slower than the L1 cache and DRAM is slower still.

All of the cores on the GPU are called threads. When writing a CUDA kernel for the GPU, you can decide: how many threads are launched, the block and grid size. Blocks are a group of threads that share a certain amount of memory (shared memory). Shared memory is not the same as the L1 cache, but for simplicity you can see it as the same (it is very fast memory compared to the L2 cache and DRAM). The grid is the total amount of blocks that are launched. When making thread blocks you have to be aware of how threads are executed on the GPU, so you can make optimal use of the GPU.

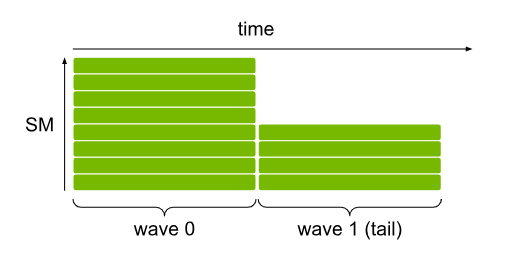

Something important to know about the GPU is that threads are executed in groups. These groups are called streaming multiprocessors (SM) and execute all threads in a group (called a wave) at the same time. The number of threads in a wave depend on the GPU (my GPU has a size of 32). To understand why this is important, lets take a look at the following image. A SM of size 8 (number of threads in a wave) is used to execute a block containing 12 threads. Because of the limited SM, only 8 of the 12 threads are executed at the same time and the remaining 4 threads will be executed afterwards. The first wave will utilize 100% of the SM, all 8 threads of the SM are active. The second wave however only has 4 active threads and utilizes only 50% of the SM. This is important to understand and be aware of when making kernels for the GPU, because you want to utilize the powerful parallel computing capabilities of the GPU to its fullest.

Shared memory

I mentioned shared memory a little before, it is an important part of utilizing the GPU for GEMM. Shared memory is very fast and shared with all threads in a block, this means that all the threads in the block can access the same memory (loading and storing data).

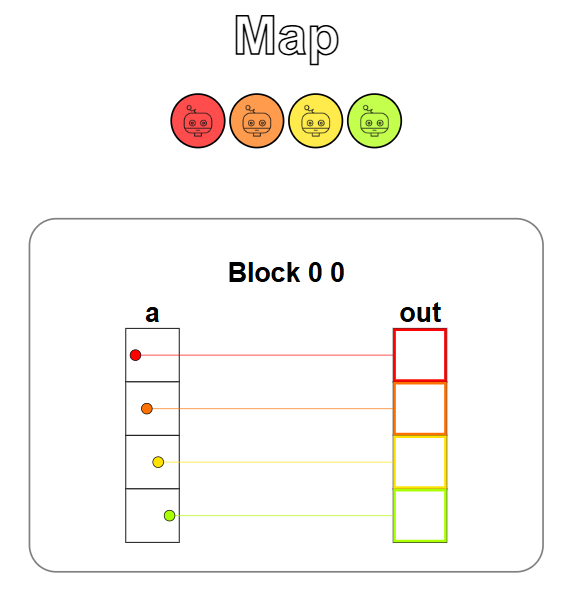

Before continuing with shared memory, lets take a look at how memory works on the GPU. Below you can see an image of a simple kernel that takes an array (a) and adds a value to each element in the array, before storing it in the output array (out). This kernel launched 4 threads (1 for each element in the array) and executes the addition for all 4 threads at the same time. The arrays a and out are stored in global memory. Per thread you load once from global memory (to get the value of the element of a), and you store once in global memory (to store the result in the right element of out).

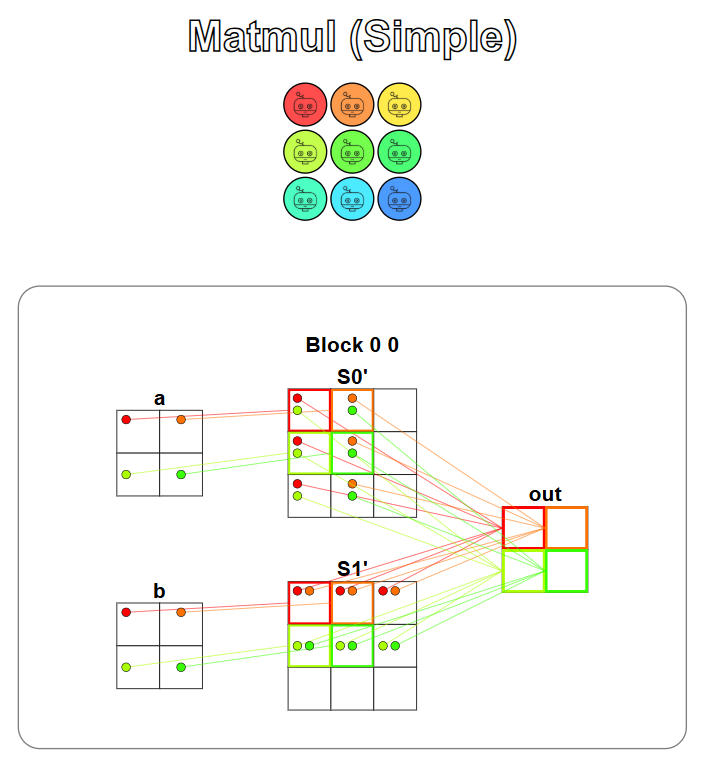

Now taking a look at a more complex kernel that does a matrix multiplication using shared memory. Matrices a and b are stored in global memory. You can read the data from these matrices into shared memory, to make them faster accessible. After reading the data into shared memory, you can use the matrices from shared memory to compute the accumulations for the elements of the output matrix (out). Each thread will:

- Read 2 times from global memory (once for each matrix);

- Write 1 time to global memory (for the output matrix);

- Read 4 times from shared memory, two elements from matrix S0’ and two elements from S1’ for the multiplication instructions (row * column);

- Write 2 times to shared memory (once for each matrix).

Performance of GEMM on the GPU

GEMM on the GPU has been optimized a lot and there are many sources online that explain different optimizations. The main source I used was: OpenCL SGEMM tuning for Kepler. It explains the concepts of the optimizations in an easy to understand and visual way. Eventhough it uses OpenCL, it is easily translated to CUDA. We will go over a couple of optimization steps, that I have implemented in my GEMM kernel.

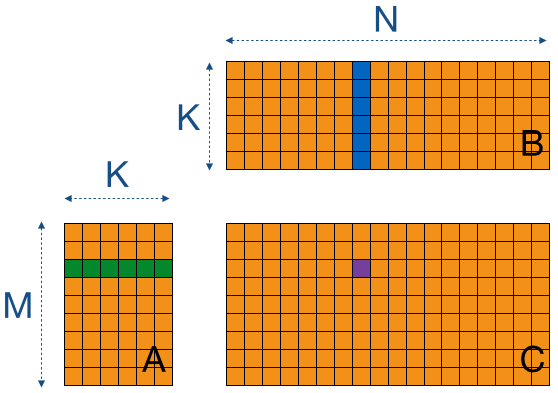

Matrix-multiplication is taking the dot product between a row from matrix A and a column from matrix B to get the value of the element of the output matrix C in the corresponding row and column. The image below is a visualization used in the tutorial that shows this concept. Implementing this on the GPU is easy enough, but it is not very fast. The reason it is not very fast is because there are a lot of global memory loads per thread.

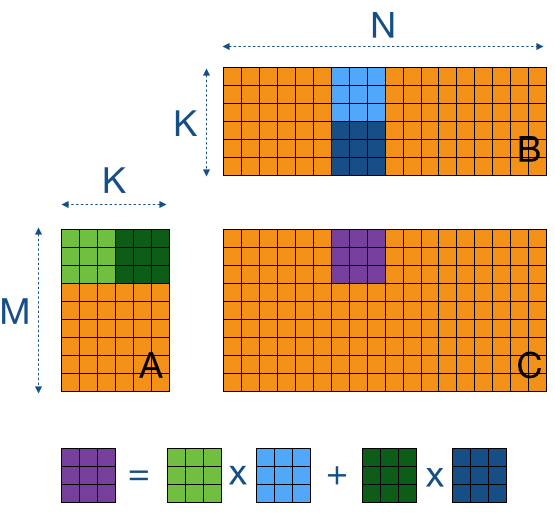

We can minimize global memory reads by using shared memory, we read sub-blocks of matrices A and B into shared memory and execute the dot product calculation for these smaller sub-blocks (tiles). We can use these tiles to step over the entirety of matrices A and B. You can set the value of an element in the tile to 0, if the tile size does not allign perfectly with the rows and culumns and has overshoot. The image below is a visualization of this concept.

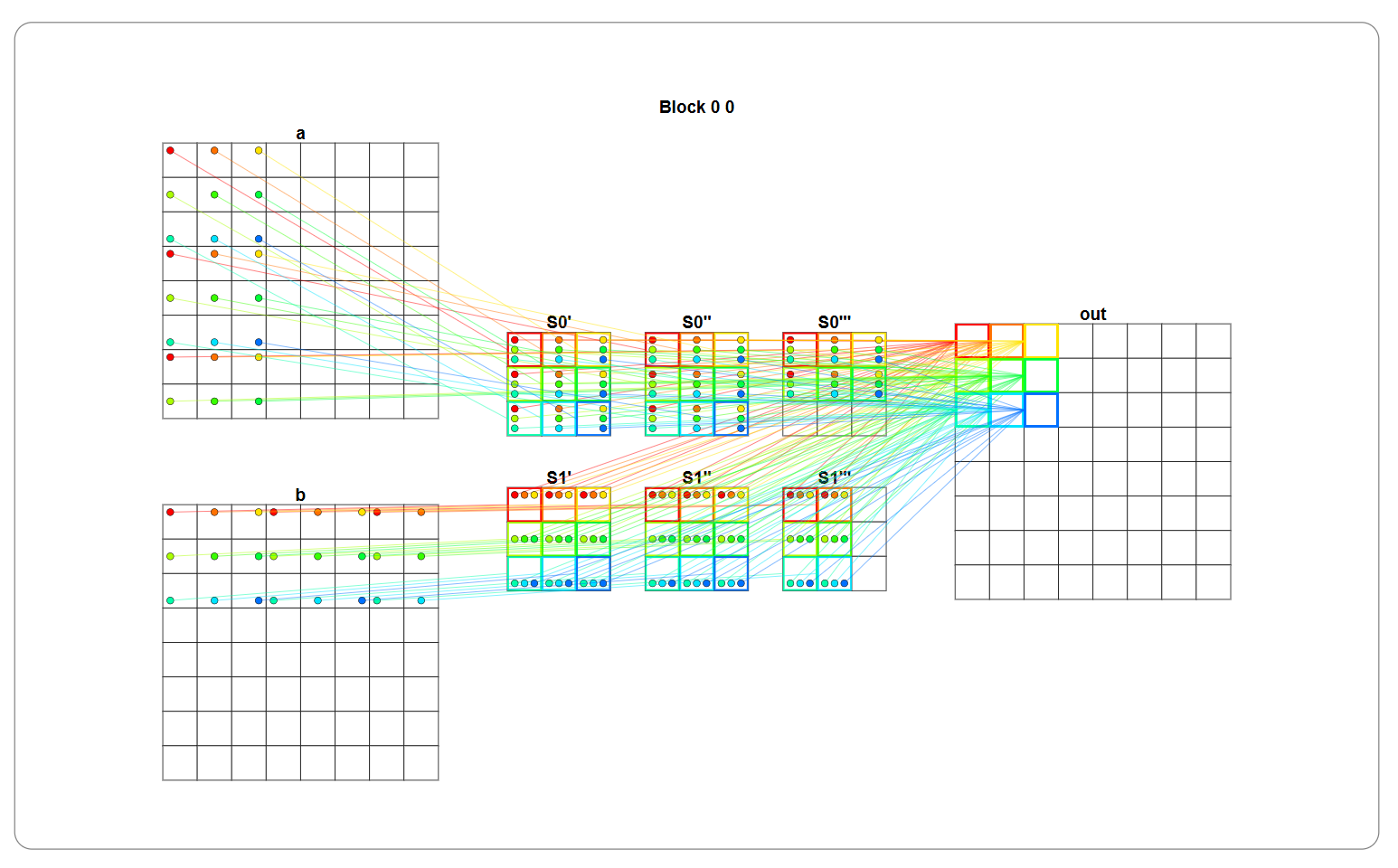

In GPU memory it will look something like the image below. This visualization shows the stepping of a 3x3 tile over the rows of matrix a and columns of matrix b. The shared memory matrices S0’ and S1’ are the tiles loaded from the orignal matrices, and are shown in the order in which they are looped through (first S0’ and S1’, second S0’’ and S1’’, third S0’’’ and S1’’’).

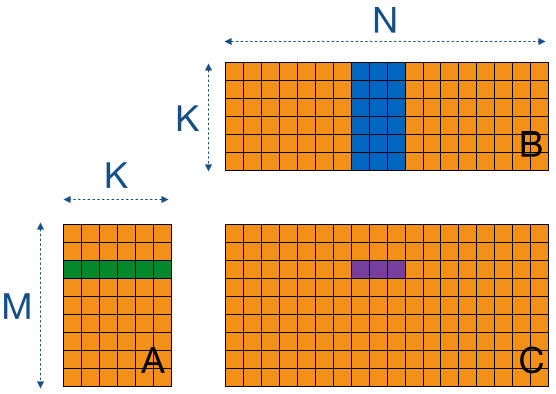

The next optimization step is increasing the workload per thread. While tile based GEMM is already an improvement to basic GEMM, it is not utilizing the GPU to its fullest. The following step makes better use of the GPU, by increasing the arithmetic intensity (more instructions per read from memory) for each thread and reducing the number of threads. In the image below, the highlighted row from matrix A has to be used for each column of matrix B, to calculate the values for each element in that row in matrix C. To minimize the memory reads from matrix A, it is possible to read the row from matrix A once and use it for multiple columns of matrix B before reading another row from matrix A. Only 3 columns are used at a time in the image below. Once these three columns have been used for the dot product computation, three new columns will be stored in shared memory.

For simplicity the example does not consider the tiling optimization done before, but the same concept of this step can be applied to the tiles used in tile based GEMM. Instead of storing an entire row and columns, you read parts of them depending on the tile size.

Utilizing GEMM for a neural network

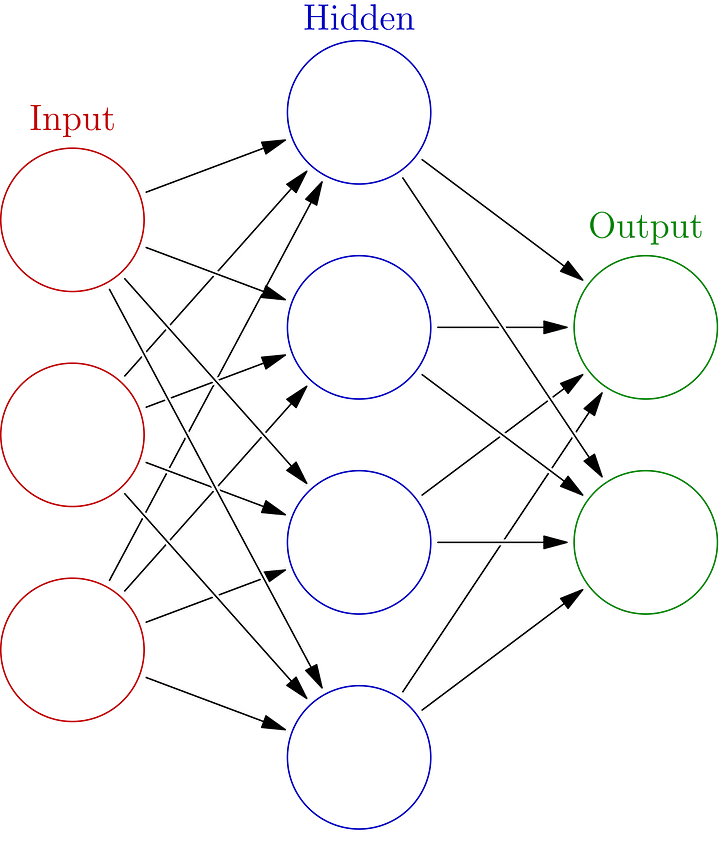

Now that we have a basic understanding of the GPU and how to utilize the GPU for GEMM, we can take a look at how this applies to NNs. The architecture of a multi layer peceptron (NN) is given in the image below. Some input goes in, passes through the NN and gives some output. Passing through the NN (forward propogation), is something that happens layer after layer, starting from the input layer, continuing through all the hidden layers and finally finishes with the output layer. The computation that happens to go from one layer to the next is GEMM and the values of all neurons (nodes in a layer) are independent from the other neurons in the same layer. So they can be done in parallel and the GPU is perfect for this.

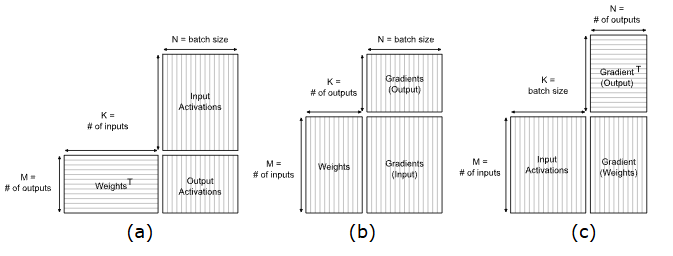

Using GEMM to move from layer to layer is the state-of-the-art method used by PyTorch, Caffe and Tensorflow according to the Nvidia documentation (Fully-connected layer Nvidia docs). The image below shows the matrices used as inputs to determine the output for different computations of the NN. Forward propogation (a) is used to test the GEMM kernel I have made, but the other computations are important for backpropogation (training of a NN).

The following code is what I have written to loop through the tiles of the input and weight matrices for forward propogation, to calculate the weighted input of the output nodes (the activation function is applied separately). This kenrel applies both tile based GEMM and a higher workload per thread.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

const int numTiles = ceil(static_cast<float>(numInputs) / tileSize);

for (int t = 0; t < numTiles; t++)

{

for (int w = 0; w < WPT; w++)

{

const int tiledRow = tileSize * t + row;

const int tiledCol = tileSize * t + col;

if ((tiledCol + w * RTS) < numInputs && globalRow < numOutputs)

sharedWeights[col + w * RTS][row] = weights[weightOffset + (tiledCol + w * RTS) * numOutputs + globalRow];

else

sharedWeights[col + w * RTS][row] = 0.0f;

if ((globalCol + w * RTS) < batchSize && tiledRow < numInputs)

sharedInputs[col + w * RTS][row] = inputs[(globalCol + w * RTS) * maxNeurons + tiledRow];

else

sharedInputs[col + w * RTS][row] = 0.0f;

}

__syncthreads();

for (int i = 0; i < tileSize; i++)

{

for (int w = 0; w < WPT; w++)

acc[w] += sharedWeights[i][row] * sharedInputs[col + w * RTS][i];

}

__syncthreads();

}

CPU vs GPU

The main reason to use the GPU for NN computations is because it is faster than the CPU, if implemented correctly. So it is important to compare the GPU implementation to a CPU implementation I had made before. To perform this comparison I used a batch size of 256 and network size of:

- Input layer: 784;

- Hidden layer: 100 (relu);

- Hidden layer: 100 (relu);

- Output layer: 10 (softmax).

I tried to utilize the SMs of the GPU to its fullest, by using a tile size based on the SM size of my GPU. I have a SM of 32 threads, so I used a tile size of 16, allowing the SMs to execute a fitting number of threads in a wave (minimal amount of inactive threads). The following table shows the results.

| Version | Duration (ms) |

|---|---|

| CPU | 22 |

| GPU (tile-based GEMM) | 43.22 |

| GPU (more work per thread) | 21.25 |

| GPU (more WPT + improved memory access pattern) | 6.5 |

The tile based GEMM implementation I had made was about 2 times slower than the CPU version. This was mostly because of a poor utilization of the GPU. By profiling the kernel (with Nsight Compute) I was able to determine the bottlenecks and improve the performance. Improving GEMM made the kernel about the same speed as the CPU version, but there were still some big bottlenecks regarding memory access patterns. A lot of time was spent idle on the threads, waiting for data. The data I stored in shared memory was uncoalesced, meaning I was accessing a value of the stored matrix, then had to jump a couple of bytes in memory to find the next value. I coalesced the data in memory by changing the memory access pattern. Now when accessing data in memory, I can read a value and the next value I need is adjacent to the read value (no more jumping of bytes to find the correct value). The resulting kernel is 70.45% faster than the CPU version, which is a significant performance improvement. There are more optimizations to be done regarding the kernel I have made, but that is for the future.

Demo

I made a small demo using the GEMM kernel for forward propogation of a trained NN, to demonstrate the GEMM kernel in action. The user can draw a digit in the ImGui window and the NN tries to classify the drawn digit in real time.